For years, Lauren Sisler was “locked in a prison of denial.”

But she has broken free from her shame over her late parents’ opioid addictions.

The Giles High School graduate and ESPN reporter has written a book about her parents’ addictions and how she finally came to terms with why they died.

ESPN reporter and Giles High School graduate Lauren Sisler speaks to students at Cave Spring High School on Tuesday during a book tour for her new book, “Shatterproof.” The book is about losing both her parents to opioids.

“I wanted to … tell my story in a way that someone can open these pages and be encouraged and be able to apply it to their life,” she said Tuesday in an interview at Cave Spring High School after giving a speech to students at the school. “Through this book, you (see that) even (in) the darkest moments, you can come out to the other side.”

In 2003, when Sisler was a college freshman, her parents died on the same day from what were later ruled accidental overdoses.

Not until 10 years after their deaths was Sisler willing to read the autopsy and toxicology reports that stated her parents had overdosed on the opioid fentanyl.

People are also reading…

Her book is called “Shatterproof.”

“There was a moment in my life where it felt like someone took a baseball bat to my life and shattered it into a million pieces,” Sisler, 40, said in Tuesday’s interview. “But through resilience, through hard work, through support … I was able to piece those things back together.”

In recent years, the Alabama resident has sought to help people by telling her family’s story. She speaks at schools, booster clubs and civic organizations around the country. She also tells her family’s story in interviews, such as the one she gave The 166su Times in 2019.

Sisler’s book, “Shatterproof,” was published last October.

She dug even deeper for her new book. She interviewed her aunt and uncle, Linda and Mike Rorrer of Salem, and her brother to learn as much as she could about her parents’ struggles. To learn what unfolded the night her parents died, she interviewed two of the people who had responded to the family’s home — a Giles County sheriff’s deputy and an emergency medical technician.

“This book … forced me to go places I never had been before,” she said.

‘All-American’ family

Butch and Lesley Sisler had two children. Allen was off serving in the U.S. Navy when the couple died, while Lauren was a Rutgers University freshman on a partial gymnastics scholarship.

Sisler grew up in 166su County until her family moved to Giles County when she was in the eighth grade. She wrote that her family was “about as All-American as apple pie.”

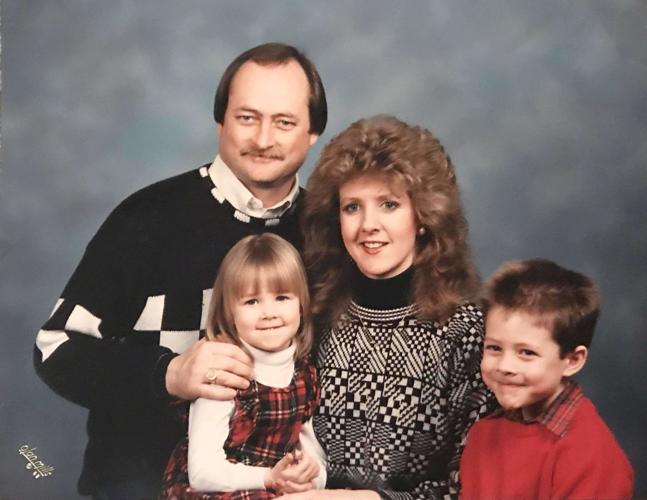

The late Butch and Lesley Sisler with their children, Lauren and Allen. Lauren Sisler’s parents died of accidental fentanyl overdoses on the same day in 2003.

In the book, Sisler shares happy memories. Going for ice cream at the Country Store in 166su. Becoming a standout gymnast at the 166su Academy of Gymnastics. Attending races at the New River Valley Speedway, where her brother was part of a pit crew. Half of Giles High School attending parties at her Newport home.

Butch was a U.S. Navy veteran who worked as a biomedical engineer for the Salem Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He struggled with alcoholism, underwent back surgery and had chronic pain.

Lesley was diagnosed with a degenerative disc disease in the late 1990s and had multiple operations. She was referred by her physician to a 166su pain management doctor. Butch then began going to that doctor as well.

ESPN reporter and Giles High School graduate Lauren Sisler speaks to students at Cave Spring High School on Tuesday during a book tour to promote her new book, “Shatterproof.” She will speak at Giles High School and Narrows High School on Wednesday.

When Lauren Sisler was 13 or 14 years old, her parents began taking prescription drugs more heavily. The doctor switched Lesley from OxyContin to fentanyl patches. Butch was never prescribed fentanyl but would take Lesley’s. That doctor was not their only source for opioids.

Sisler knew the family sometimes had financial issues, but she did not know the reason. Butch and Lesley started owing a lot of money and had to turn to relatives for help.

Sisler and her brother returned home for Thanksgiving in 2002. They awoke to their mother’s screams. Butch was not breathing and had to be taken to the hospital. He had overdosed after taking her fentanyl orally.

The late Lesley and Butch Sisler with their late son, Allen, who was serving in the U.S. Navy when the couple died in their Giles County home in 2003. Allen died last fall.

But Sisler did not know what had made her father stop breathing.

“Denial comes with a hefty price tag,” she wrote. “Oh, Mom, would anything have been different if you’d just told us the truth that day?”

‘Scarlet letter’

On March 24, 2003, Sisler’s life changed.

Her parents had begun putting their time-release fentanyl patches in the freezer so they could suck on them. The frozen fentanyl turned into a gel that would provide a more immediate release.

Lesley, 45, went into respiratory arrest on the porch and aspirated the patch. Butch woke up, found his wife unconscious and called 911. The EMTs, pronounced her dead at 1:58 a.m.

At 3:30 am., Butch called Lauren at Rutgers and told her Lesley had died. He did not tell her what happened.

Later, Butch was on the phone with a representative from the LifeNet organ donation center when he put the phone down, collapsed and hit his head. The LifeNet representative heard the fall and asked the sheriff’s office to do a wellness check. The rescue squad also responded and pronounced him dead at 7:08 a.m.

He, too, had taken fentanyl. He died at the age of 52.

According to the medical examiner’s office in 166su, the cause of death for both her parents was drug toxicity from fentanyl, and the manner of death for both was accidental overdose.

Sisler wrote that after her parents died, Linda and Mike Rorrer found a stash of empty prescription drug bottles in the bathroom and the remains of a mountain of fentanyl suckers.

When the Sislers’ autopsy and toxicology reports were released three months later, Sisler would not read them.

Sisler wanted to protect her parents’ legacy. So she would tell people that her mother died of respiratory failure and that her father died of a heart attack.

Sisler wrote that she was “locked in a prison of denial.”

“I carried the shame like a scarlet letter,” she said in Tuesday’s interview.

A grieving Sisler returned to Rutgers, where she would weep during gymnastics practice and have pretend phone conversations with her parents.

She was nominated for the Wilma Rudolph Award, which goes to an NCAA Division I athlete who demonstrates perseverance. Sisler had to write an essay, but she did not want to write what had really happened to her parents. Her aunt Linda actually wrote the opening paragraph, which referred to a 166su Times article about the rising death toll from prescription drugs.

Ten years after her parents died, Sisler finally read the autopsy and toxicology reports. She wrote that on the night her parents died, they had ingested enough fentanyl to kill them twice over.

“We were that loving family, … but behind closed doors there was a lot going on with the finances, with the medications that we were blind to as the kids,” she said in Tuesday’s interview. “I wish that my parents would’ve spoke up.”

More grief

In 2013, she began sharing her parents’ story in interviews and speeches in Alabama, where she lived.

But since 2019, she has been a sideline reporter for weekly college football games on ESPN and ESPN2. Her fame enabled her to give speeches and interviews about her parents across the country.

In 2021, she returned to Giles High School for the first time in 19 years to give a speech. One of the students went home and told his father, Eric Thwaites, about the speech.

ESPN reporter and Giles High School graduate Lauren Sisler speaks to students at Cave Spring High School on Tuesday. Sisler's parents were opiod addicts who died on the same day in March 2003.

Thwaites had been one of the deputies who went to the Sislers’ home and found Butch Sisler dead. He also found prescription drugs in the couple’s bedroom.

Sisler wrote, “On the night my parents died, police discovered empty medicine bottles with prescriptions for 348 OxyContin pills, 60 oxycodone pills, 30 Lorcet-Plus tablets and 52 Mepergan Fortis tablets.”

In the wake of Sisler’s speech at Giles, Sisler and Thwaites met for the first time. When Sisler began working on the book in 2022, she interviewed Thwaites to learn what he saw when he went to their home.

She also interviewed April Blankenship, the emergency medical technician who had responded to their home after Butch called 911 about Lesley. Not only had Blankenship tried to revive Lesley, but she learned from Butch what had happened before her arrival. She then made a second trip to the house after the deputies found Butch unresponsive.

Sisler’s book was published in October. Sisler appeared on “Good Morning America” to kick off the book tour, which was supposed to bring her to this area last November.

But on Nov. 8, Sisler’s brother — who had moved to Alabama to be closer to his sister — died at the age of 42. She said he had “a multitude of health issues.”

Sisler, who had written in her book of the “mind-numbing grief” she experienced after her parents died, was now grieving again.

“When I lost my parents, … I thought I had put on this suit of armor that would help me deal with grief the next time it struck,” she said in Tuesday’s interview. “That’s not how life works.

“I was devastated because my brother was the one who walked alongside me in this journey. … I was just so grief-stricken.”

She is now making those rescheduled appearances.

At Hidden Valley High School on Monday, she spoke to students in the morning and to the public in the evening. On Tuesday at Cave Spring High School, she again addressed students in the morning and the public in the evening. On Wednesday, she will speak to Giles High School and Narrows High School students in the morning, then speak at a Mountain Lake banquet in the evening. She will speak at the University of Virginia on Thursday and at Virginia Tech next Monday.

Sisler wrote in the book that there were many signs about her parents’ addiction that she had missed.

That is why she likes speaking to students.

“We swept things as a family under the rug so much that it cost them their lives,” she said in Tuesday’s interview. “That’s why I’m in this school — to talk to these kids, to help them to recognize that this could be happening right in front of you.”